What is a climate refugee?

This is an assignment I did for a MOOCs course run by the University of Melbourne in 2013. It in many ways echoes the present so I want to add it to my blogs. I worked hard but got 95% for my efforts. Getting a graphics to fit from my PDF file was difficult.

The IPCC report of September 2013 shows a 90% certainty that the rate of increase will be greater than 2007 projections. Revised predictions are in the order of 45-82cm higher with no mitigation by the end of the

The new IPCC6 projections for the average sea level (see right) in the period 2080-2100 are greater than in the 2007 report, ranging from 45-82cm higher than the present if nothing is done to curb emissions to

Refugees

have been traditionally thought of as stateless people fleeing from wars and

persecution. Forced Migration is a related term that was used in a recent

report by the Environmental Justice Foundation1 on the

impact of climate change in Bangladesh. Indeed this report is a good start to

learning about the impacts of global warming on the most vulnerable of

communities in the Indian subcontinent.

Whether climate refugees or forced

migrants we are talking fundamentally about survival, not a better life but

almost any life at all, and the likely permanent displacement of people from

their homes, communities, and nations due to rising seas. In 1990 the IPCC

declared “that the greatest single consequence of climate change could be

migration. 2” Estimates of between 150 – 200 million climate

refugees by 2050 are common3 making it a

massive challenge for policymakers and concerned people around the world.

However the

term climate refugee is in dispute. The UN Convention Relating to the Status of

Refugees doesn’t yet provide long-term legal protection to refugees affected by

environmental change4 leaving their status in a kind of limbo. The

International Organisation for Migration in the interim proposes3 defining

climate refugees as those “... obliged to leave their habitual homes either

temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their country or

abroad.”

Sadly a

small element, in Australia anyway, has an “us and them” attitude and tends to

think of them as “gatecrashers to our

party”, or as uninvited aliens who alarmingly steal across our borders to

burden us with their needs. But climate refugees can reside within these same

borders. Think of the Oklahoman tenant farmers of the 1930s dustbowl fleeing to

California so well depicted in John Steinbeck’s classic novel, Grapes of Wrath,

or of a predicted relocation of farmers from southern Australia to the north.

Both are clear instances, past and future, of the consequences of environmental

devastation.

Looking far

beyond our borders today we also have Newtok, Alaska5 which is

seriously threatened by rising seas and the imminent losses of home and

livelihood. And let’s not forget New Orleans post-cyclone Katrina and any

number of other places ravaged of late by “natural disasters”. Witness also the

Queensland floods and the Victorian bushfires to get a wide perspective of

alarming possibilities.

Swamps or

deserts

Climate change threats I will examine include:

-

Rising sea levels leading to a loss of habitable, cultivable land, and

freshwater reserves.

-

Changing weather patterns that can turn fertile farmland into deserts

or flood plains

Swamping sea

levels – the new wetlands

As

indicated above rising sea levels are already impacting on communities in

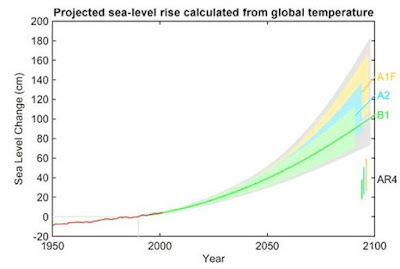

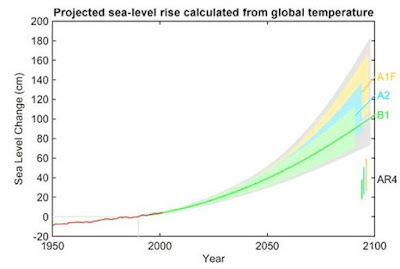

Bangladesh and Alaska. The IPCC in their 4 th Assessment

in 2007 presented various scenarios, see below, with projected rises of between

50 cm and exceeding 1.4 metres by 2100.

Projection of sea-level

rise from 1990 to 2100, based on IPCC temperature projections for three different emission

scenarios in 2007

report. From skepticalscience.com

Projection of sea-level

rise from 1990 to 2100, based on IPCC temperature projections for three different emission

scenarios in 2007

report. From skepticalscience.com

Projection of sea-level

rise from 1990 to 2100, based on IPCC temperature projections for three different emission

scenarios in 2007

report. From skepticalscience.com

Projection of sea-level

rise from 1990 to 2100, based on IPCC temperature projections for three different emission

scenarios in 2007

report. From skepticalscience.com

The IPCC report of September 2013 shows a 90%

certainty that the rate of increase will be greater than 2007 projections.

Revised predictions are in the order of 45-82cm higher with no mitigation by

the end of the

The IPCC report of September 2013 shows a 90% certainty that the rate of increase will be greater than 2007 projections. Revised predictions are in the order of 45-82cm higher with no mitigation by the end of the

century, to

26-55cm if carbon emissions are controlled or reversed. Such increases would be

catastrophic threatening major cities such as Shanghai to New York with

hurricanes and cyclones causing enormous damage to coastlines.

The new IPCC6 projections for the average sea level (see right) in the period 2080-2100 are greater than in the 2007 report, ranging from 45-82cm higher than the present if nothing is done to curb emissions to

26-55cm if

carbon emissions are halted and reversed. Without abatement sea levels could

rise by a 98cm, or 16cm higher than in the 2007 predictions (see above) which

were bad enough.

It gets

worse. Exactly how fast glaciers and ice sheets break off into the sea remains

the subject of ongoing research and are not factored into these IPCC estimates.

They could add many centimetres to the

rise in sea levels if the large

Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets melted rapidly7. A time

and policymaking framework can begin to be deduced from the above figures for

coastal protection, an extremely expensive undertaking, especially for

developing countries. For example, by mid-century average sea level rises could

exceed 20 cm which would present problems for many low lying Pacific islands

some of which would cease to exist. Climate data sourced is from satellite

surveillance, sea buoys, weather stations, analysis of ice cover and diminished

albedo, etc and the models from this data quite sound. Technology to retrieve

such data, eg from satellites, is in some cases relatively recent.

Which

countries are most vulnerable?

Whilst

Bangladesh, Pacific islands such as Tuvalu, and the Maldives come immediately

to mind other countries most at risk are listed in the following table. Note

that they are among the poorer ranking and least polluting countries of the

world and that The Netherlands, Venice/Italy, and metropolises like London face

fewer threats due to their greater adaptive capacities.

I love a sunburnt country, a land of sweeping plains

Of rugged mountain ranges, of droughts and flooding rains

Dorothy Mackellar

According to Thomas Stocker, co-chair of the IPCC

working group on physical science:

"Heatwaves

are very likely to occur more frequently and last longer. As the earth warms,

we expect to see currently wet regions receiving more rainfall, and dry regions

receiving less, although there will be exceptions,"

This essentially means more rain in

the tropics, less in the middle latitudes and more rain closer to the poles.

Australian agriculture, in the tropics and middle latitudes, faces challenges

in drought, water security, low soil fertility, weeds, and a changing climate.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) has

forecast the global warming will result in decreased rainfall over much of

Australia exacerbating water availability and quality for agriculture7. A

temperature rise of between only 1 - 2o Celsius,

the CSIRO predicts8, will result in a 12–25% reduction

in flow in the Murray and Darling River basins. Many farmers and rural

communities depend on water from these major river systems and angry scenes

including the burning of reports over threatened reductions to water quotas

have made the evening news. Often forgotten by contesting groups are the needs

of the rivers to maintain strong water flows.

An adaptive strategy has been

proposed in various quarters that some agricultural enterprises may need to

relocate to the tropical north, where increased rainfall is predicted, but of course

the very same rainfall carries a risk of flooding. Nevertheless, Australia has

an adaptive capacity that far exceeds that of our near neighbours in the

Pacific desperate for our help and understanding.

Disasters

can manifest in the short term by sudden events like storms and flooding, or be

long and more drawn out by extended heat waves and drying up of crops, soils

and so on, perhaps even leading to a dustbowl as experienced in the 30s in

Oklahoma. We need to focus and plan ahead for what science has so clearly

predicted, be it to our farmland or to our coastal properties.

Justice and

human rights

No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of thine

own were; any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

John Donne

As Professor

Jon Barnett proposed in his lectures climate change is a social problem induced

by people. Thus solutions should be sought in the best interests of humanity at

large and not be lost in the rhetoric of border protection and xenophobia so

evident in some quarters today. It is clear from the table above that most

global emissions come from affluent societies that have gained most from

industrialisation and rising consumerism. The poorer less polluting countries

are mere innocent bystanders of our carbon-emitting frenzy. This, therefore, is a

justice and human rights issue we cannot ignore when climate refugees wash up

on our shores in boats or less conspicuously in arrival terminals in our

airports. Equally important is aid to assist them improve their adaptive

capacity.

The

wealthiest 10% in developed countries emit 7.5 times more CO2 than the poorest

10% in developed countries and 155 times more CO2 than the poorest 10% in

developing countries (Baer).

In Article 3, on Common but differentiated responsibilities,

the UNFCCC states: “Specific needs and special circumstances of developing

country parties ... those that are particularly vulnerable ... and that would

have to bear a disproportionate or abnormal burden under the Convention.” (3.2)

Article 4

on Commitments further states “... assist the Parties that are particularly

vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in meeting the costs of

adaptation (4.4). Thus a key feature of the 2009 Copenhagen Accord is a green

climate fund, to support action on mitigation and adaptation with a target of

US$100 billion p.a. by 2020. Finally smaller states through coalition-building

have gained a voice in climate conferences albeit a small one. They should be

heard and supported.

All fine

words no doubt but will the green climate fund deliver in the face of economic

downturns and budgets restrictions, and locally how will these climate refugees

be met when they wash onto our shores with absolutely no rights or long term

legal protection? Will compassion overrule xenophobia and self-interest in our

future refugee debate or will climate refugees be left to fester unaided?

Current Australian politics is

particularly worrying on this matter. Climate change abatement is basically in

the balance and scaremongering slogans of border protection abound from shore

to glittering shore. I taught ESL to adult migrants and refugees for almost 30

years, years of wars, repression, and at times of heartbreaking prejudice

before final resettlement in this our lucky country. Most migrants and refugees

have gone on to better lives and to making worthwhile contributions to life

here, none more so that Akram Azim, the current Young Australian of the Year

who arrived as a 12-year-old refugee from Afghanistan and has worked to give a

voice to young indigenous people.

One can only hope that the climate

settlers of the future will not be treated with the disdain and prejudice that

greeted the Joad family (from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath) in their epic flight

from the dustbowl of Oklahoma to the fruitbowl of California, an environmental

tragedy of the Depression era that displaced tens of thousands of drought

stricken farmers. Perhaps the homeless denizens of New Orleans fared better

after Cyclone Katrina broke the levees and swamped their homes. Will we warmly

welcome climate refugees borne here by the high seas or the arid earth of

climate change? Or will the world become a much sadder place for our loss of

humanity, a crowded but lonely planet?

1860 words.

1.

Environmental Justice Foundation, 2012. A Nation Under Threat: The

impacts of climate change on human rights and forced migration in Bangladesh.

See http://ejfoundation.org/climate/a-nation-under-threat

2.

Warner K and Laczko F. (2008). ‘Migration, Environment and Development:

New Directions for Research’, in Chamie J, Dall’Oglio L (eds.), International

Migration and Development, IOM

4.

Hartley, Lindsey. (16 February 2012). Treading Water: Climate Change,

the Maldives, and De-territorialization. Stimson Centre.

5.

Guardian report, America’s first climate refugees, at http://tinyurl.com/lbss4xc

6.

International Organisation for Migration proposal. PDF at http://tinyurl.com/mohmn2a

7.

http://tinyurl.com/pjb9dsf IPCC climate report: the digested read, UK Guardian, 28

September 2013

8.

Summary for policy makers: www.climatechange2013.org/images/uploads/WGIAR5-SPM_Approved27Sep2013.pdf

9.

Preston, B.L.; Jones, R.N. (February 2006). "Climate Change Impacts on Australia

and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas

Emissions". CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009.

Retrieved 2009-01-25.

10.

CSIRO Arnell, N.W. (1999) Climate change and global water resources.

Global Environmental Change 9, S31-S46.

Comments

Post a Comment