In memoriam: my Father and Mother

The years go by, and suddenly the 50th wedding anniversary approaches. That was the case with my sister Carmel when I rocked up in Perth in early December 2017 for a celebration and family reunion. I missed the wedding in 1967 but I wasn't to miss this gathering, or else.

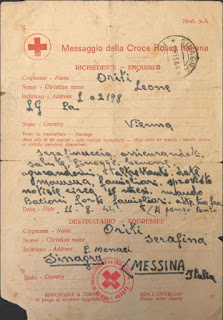

The years go by, and suddenly the 50th wedding anniversary approaches. That was the case with my sister Carmel when I rocked up in Perth in early December 2017 for a celebration and family reunion. I missed the wedding in 1967 but I wasn't to miss this gathering, or else.As often happens on such occasions old family photo albums are dusted off and revisited, for selections for a PowerPoint presentation in this case but also to reminisce on past lives, and memories. A document emerged and captured our attention. It was an old, yellowing, fragile and fading Red Cross document dated 11 August 1944 and sent from Vienna to my mother informing her that her husband, our father, was alive as a POW. Headings in this message form were in both Italian and English, and there was space for the handwriting of up to 25 words that were only to be family news of a strictly personal character. Please write clearly, it admonished.

Our father, Leone, rarely spoke of the war, but at the dinner table, when we were reluctant to eat what was served up he would, like parent everywhere, bring up the starving children of the world. Sometimes he went further and talked of the cold, starvation and hunger he experienced as a POW in, I recall Germany. According to Carmel it was in Montenegro, in the then Yugoslavia. The Italian Red Cross message was from Vienna and gave dad’s address as L 02198, which like a postcode most likely designated the camp of his wartime internment.

We struggled to decipher the 25 word scrawl but we extracted the gist of the message especially the concluding “I think of you often”. The message to our mother, Serafina, began with the term of endearment, Serafinuccia. We were intrigued and didn't fully understand how an Italian soldier ended up as a German prisoner of war, but of course many Italians opposed fascism, and dad was a socialist party activist in his day, which may partly explain it. After the fall of Mussolini, and the consequent rupture of the Axis Power in Europe, many Italian soldiers were undoubtedly rounded up for internment in the work camps of the 3rd Reich, and my father was very likely one of them, and whilst this was a difficult period for dad and mum it paled in comparison to the death camps of the holocaust.

Apart from his politics Leone Oriti was somewhat suspicious of Catholic priests who he would label as mafiosi: this recollection is disputed by my sister Carmel who says he was just retelling typical jokes of the time about the clergy. Our mother remained a loyal member of the Catholic flock, as indeed does Carmel.

Dad often condemned the US for their indiscriminate bombing of everything, anywhere, saying that nothing was sacred and everything was targeted. This was perhaps a foreshadowing of my experience in the Vietnam War, and of the intense bombing by the US Air Force there, which I have written about in another blog The 60s, the Vietnam War and me. It is said that things change but, paradoxically, remain the same. This quote comes out of the mouth of Burt Lancaster in Visconti's film The Leopard that is set in Sicilian history at the time of Garibaldi.

Dad was a bit of a joker, a clown, a lad, and he was given the moniker Garibaldi, although in Sicilian it sounded like Garibuddi. I had to check and was told that his nickname was indeed that of the very same Guiseppe Garibaldi whose statue can be seen throughout Italy. Dad’s political philosophy was very much that we were continuously being screwed by the rich and had to look out for ourselves. As far as I know, he always voted Labor.

Our mother Serafina, by contrast, was less vocal, and certainly less of a social animal, unless it was in English which she went to greater lengths to learn than dad, and she cherished every opportunity for conversation. She could talk you under the table and had a lot to say. I remember accompanying mum as a young boy in shorts to evening English classes, and to hearing her practice her English correspondence lessons via radio broadcasts, a foreshadowing perhaps of my future career as an ESL, or Adult Migrant English teacher.

Dad just muddled by in a Me-Tarzan-You-Jane fashion which became more pronounced as he aged. But he was always a keen reader of the morning paper, The West Australian, which I often had to wrestle him for as he dunked his milk arrowroot biscuits into his tea, prior to his setting off to work for the day, often in the dark. And he wrote all the family letters. according to Carmel.

Generally, however, they were chalk or cheese: mum the introvert and dad the extrovert and lad about town.

Dad had a few party tricks that amazed us as kids. Sometimes he liked to play the magician and making things disappear before our eyes delighted him no end. His limited English wasn’t up to reading bedtime stories to us but we always had reading material apart from the morning papers, especially weekly boys-own comic subscriptions that he paid for. There was no TV back then so inevitably the pack of cards came out for evening entertainment, in particular, the Italian games of Scopa and Briscula. There was no holding back the intense rivalry to win those prized matchsticks, which is how they kept the score as Italian radio played music indifferently in the background.

There wasn't a lot of money and we weren’t given pocket money as such but had to ask for funding for the particular occasion. Dad was the soft touch and we often started negotiations by saying, or plain lying: “Mum says it’s ok to go to the movies but asked to check with you.” Hands out. Generations of kids have successfully rorted their parents in this duplicitous way.

Although a soft touch dad didn’t call all the shots. He did his share of cooking, both indoors and especially BBQs, and most of the work in the garden which he loved and tended like a mistress. He went from working in factories and building sites to developing skills as a stonemason, which is hard, tiring work; to growing flowers which he serenaded and sold at Perth produce markets. I’ll always remember him humming around in his shorts, singlet and thongs in the Perth heat. Singlets, shorts and thongs were his summer uniform, and sometimes in summer school holidays, he had work near the beach and let us come along, and often other kids in the street also packed bathers and towels and crammed into the black FJ Holden, dad's first car, for such a day out. How good is that! He worked away while we frolicked and swam, only taking a break to join him for lunch. Footloose and free. What great summer escapades!

Certain Italian traditions held sway in our household. The annual winemaking, always a rough red, was top of the list and no visit to our place was complete without a trip to the cellar and a tipple or two. We never saw the process as dad and his mates simply bought a quantity of grapes, and someone else produced the wine to order, so no stamping on grapes for the vino, but a remote wine press to do the job. It was obligatory to sing the praises of your wine to visitors, be it poured from a bottle or pulled from a barrel. But let’s be frank, it was all about bragging rights. Dad took great pride in the red wine he bottled, but in my case, I developed a lifelong preference for blanc plonk, as wine was called in the conservative 50s and 60s.

In our second and final home in the Perth suburb of Dianella dad had the obligatory cellar that also stored other handcrafted delicacies, like bottled tomato sauce. It was the culinary centre of the household and there was an annual ritual to make and bottle tomato sauce, but I never liked the smell of the occasion. But just buying tomato sauce would have been unthinkable. As a kid it never happened. Our family shared the great Australian dream of home ownership, and skimping and saving every penny for this ultimate goal was a big deal indeed, and homemade was the answer. Pickles and sausages also shared space, time and economic reckoning. Out of the oven in the early days came hot, home-baked bread but after a few days it grew stale but we still had to eat it without complaint. No dinky di Italians could live without fresh pasta and that also became a homemade product, drawn out like knitting. Sliced bread and pasta were never on our shopping lists for many years. Until our great Australian dream home was built, and we had a very proper mortgage hanging around our necks, like everyone else, we had to do it ourselves in the kitchen, cellar, and garden. Such is the frugal life of the settlers, especially the southern Italian variety.

In those times we didn't have toasters for stale bread or fridges for frozen ice cream, absolute essentials today. It's hard for our kids to imagine the daily ice block delivery for the family icebox. These ice blocks were the size of a small esky so it was hard work for the icemen. I remember one day I got my head trapped under our icebox; don't ask me how but if anyone could do it I could. I was mightily relieved when I got my head loose, fortunately, withour the assistance of mum and dad.

In those times we didn't have toasters for stale bread or fridges for frozen ice cream, absolute essentials today. It's hard for our kids to imagine the daily ice block delivery for the family icebox. These ice blocks were the size of a small esky so it was hard work for the icemen. I remember one day I got my head trapped under our icebox; don't ask me how but if anyone could do it I could. I was mightily relieved when I got my head loose, fortunately, withour the assistance of mum and dad.

Mum and dad came from essentially peasant backgrounds - landed peasants with small holdings that were divided with each succeeding generation - and no house was complete without a beloved garden, and dad, as king of the Oriti castle, tended his most assiduously. It was the pride and joy of his earthly empire and he was never happier than when he did its bidding. I remember the day his mates assembled and, after a lot of digging, sweat and hard yakka, bored and put down a well. A sprinkler system with timers was attached shortly after. The sprinklers were switched on like clockwork to water his precious lawns and garden, and I recall with amusement his muttering on a visit as a widower many years later that: “X has probably forgotten to turn the sprinklers back on as instructed”. So he rang to double check on the health of his garden, of his beans, carrots, lettuce, tomatoes and whatever else he could coax from the manure in the ground. We were relieved as he was a short step away from catching the next plane back to Perth, to attend to his beloved crops.

Dad greatly valued his very fresh vegetables but exotic flowers including orchids also bloomed under his care. After he retired or semi-retired, he would load his trailer and sell these pots and plants from his stall at the markets, a small-time trader as it were. The great and wise French philosopher Voltaire said in his famous book, Candide: For true happiness, you have to tend your own garden, and dad certainly did that as his highest priority. That wonderful film 1979 comedy, Being There, with Peter Sellers sends the same message about those who tend the earth wisely.

We tread softly in his garden but not on his lawns where it was a free for all, wrestling and all the other entanglements of kids on the loose, be they Tarzan or Robin Hood.

Every house in Perth had at least one lemon tree, and no doubt still does. We also had extensive grape vines but generally, birds beat us to those lovely bunches of grapes, despite dad's spraying and netting. At the end of the garden was the dunny, and on wet nights we had to dash down that long path to do our business, in the dark.

But some fruit came from a nearby neighbours fig tree. For a modest payment, mum and dad would go with their buckets and pick their own figs, which they devoured with relish. We kids would devour with relish mulberries from the overhanging branches of a neighbour's tree and was it messy with the telltale red juice all over us.

As a stonemason dad also had artistic talent with his hands turning out ornate stone artwork for our home, and which decorated the homes of others. He built classy feature walls, popular at the times, that competed for attention with paintings hanging nearby. He generally knew his tools and yielded them with dexterity. Dad will always be the DIY king in our family. Sadly his green fingers and steady grasp of tools weren’t passed on to me, or should that be us. Like my brother Sam I have good digital skills but like Woody Allen I’m “at two with nature”. Also like Woody Allen our family's ethos was that it was dumb to buy retail and insane to pay rent. Pretty average views these days of sales and high home loans.

We had no pets but kept chooks which were much more common back in 50s backyards. Apart from the eggs, some made it into the oven after some messy off-with-the-head and plucking of feathers. Chicken was an expensive luxury in those days and they graced the Christmas table and on other important dining occasions. There were no supermarkets then and people went to the Perth CBD to do their weekly shopping. How the world has changed!

Our milkman delivered fresh milk in the very early morning on a horse and cart. I waited for him and he let me come along until I invited some other kids along and those rides soon stopped. Some bread deliveries in the neighbourhood were also by horse and cart.

When I was about 12 dad had this idea of moving out of the suburbs and buying an orchard, and whilst we had certain romantic notions of country life, we loved visiting an orchard belonging to some family friends who dad had helped shop for implements when they first arrived in Australia, but this tree change was not going to happen. We all, mum included, voiced our shrill opposition. We clung to the suburbs, and for family peace and harmony dad gave up his dream of a rural retreat and an earthy independence. Moving and building our own home remained the absolute bedrock of our existence, and the search for a city block for this dream home remained the holy grail of the good life in Australia. And when the time came dad would be ready, with sleeves rolled up, to assist with construction. Once again frugality ruled and all spare change went into the housing fund. Nothing quite like having an Oriti roof over your heads. When the time did come I'd nagged my parents into letting me join the army and had moved to NSW. I never saw it's construction, assisted by his mates brick by brick, and mum and dad had a hard year in 1968 when I was sent to Vietnam.

Mum suffered bad migraines that led her to retreat to her bedroom when they unsettled her. She didn't suffer them quietly, had quite a temper but nevertheless led the home support team, never having a job during my childhood that I can recall. Stay-at-home mothers were relatively common in those days. It’s embarrassing to reflect on how my two brothers and I lazed about, often aimlessly, and were never given family chores whereas our sister Carmel had to pitch in to do the housework daily. Beyond the white-picket fence, male chauvinism ruled in Menzies’ Australia, on both sides of the cultural and political divide. However mum didn’t take any crap from dad. Ditto Carmel in her marriage.

Back then we boys could go out and play wherever we wanted as long as we were home for dinner. We roamed far and wide, often in bare feet in Perth’s hot summers, no thongs for us, nor sun hats: there were no safe houses then. On hot days the steamy footpaths and asphalt roads scorched the soles of our feet causing us to do the barefoot shuffle and dart from shade to shade for relief, and at other times the bindies in the innocent grass took over the torment on our bare feet. We were able to climb every tree in a large nearby park - a boys rite of passage - and we also explored and hung around the muddy foreshores of the Swan River: questions were rarely asked about our whereabouts and how far away we had wandered. It's a wonder that kids survive childhood. I remember one occasion near the Swan River when Tony or was it Sam, fell into a creek and foundered for what seems ages before we thought to pull him out of the water and avert his drowning. We were more worried about mum's finding out than anything else. But at night and after dark we were home, no ifs and buts. The world was our oyster, but it wasn't the same for Carmel. Teenage girls were kept on a leash.

Mum loved singing and how could I forget her ringing alto, at least it sounded loud, when she hung out the washing and did other housework. I only sing in the shower myself but mum was a songstress and opera and Sicilian folk music ruled. I recall Mario Lanza being in the mix somewhere, but it was from radio as we had no records at all. I was sometimes asked to help mum fold the dried sheets off the Hills Hoist in our backyard. I would tightly grip the sheets with mum violently pulling and stretching them until they flew out of my hands. Mum was shy and introverted but she wasn’t shy when it came to singing. Mum’s singing is probably where Carmel got her lifelong love of music, a notable feature of her life and personality. Mum had perfect skin and never wore makeup. Carmel the same.

There was no TV and mum and dad resisted buying a set when television first arrived in Perth. Of course those bulky boxes were ridiculously expensive when the black and white television era began, but mum and dad said that they would just distract us from our homework. Interestingly once we had left home, and they finally bought a colour TV, mum in particular, became quite a TV addict, often dozing in front of the box and reacting angrily when someone dared switched it off and wake her up. She loved wrestling, quizzes and would you believe cricket, anything with an outcome, and any winner she could cheer on and triumph with.

At night we listened to the radio, especially radio serials like Dad and Dave, and Larry Kent Detective, but we also loved going to the flix at every opportunity. Victor Mature, a well-known movie idol in the 50s, bore a strong resemblance to dad in many ways, so much so that and I came to think of them as twins and this, our Hollywood connection! Like Victor Mature dad shaved daily, unlike my brother Sam and I, and he had a full head of hair to the very end of his life. We boys are like chips off the old block in the hair department.

On the female side, in addition to hitting those high musical notes, and that good skin, mother and daughter were alike in other ways: they had similar temperaments and struggled with increased dress sizes, and they weren’t silent when occasion permitted opinions to be exchanged and lines drawn. And they went to church on Sundays. Carmel came to drive but mum never learnt to drive and wasn’t disposed to do so. She retained the front passenger seat.

The biggest difference between mother and daughter was in the kitchen. Mum was an indifferent and boring cook and vastly different to Carmel who is truly a gourmet queen who can conjure up all kinds of exotic dishes, almost at the snap of her fingers. But mum made a special effort on birthdays and other important occasions when she turned out her signature dishes that were greatly anticipated, like her take on lasagna, or pasta forno, and cannoli.

We kids never had a bedtime or bedtime stories for that matter. We simply dragged ourselves to bed when we were ready for sleep. When one of my brothers fell asleep anywhere we were expected to assist him to bed. Often the youngest, Sam, would fall asleep or start drooping. Kids can be so cruel. We would lift and drop him, sometimes from considerable heights, hilarious, and then get a kick out of seeing his body bounce off the floor. Sorry Sam from big brother. It’s amazing that you’re still alive today bro, perhaps because we toughened you up for the duration. Another story to recount is a night I was doing my homework and Sam was interrupting me. After a few warnings I let fly with a compass and to my amazement, it hit him square on the bum. It didn't quiver like an arrow but it hung there and after the shock, we had to laugh. We never told mum and dad about this compass throwing incident.

In the 50s there was post-war chain migration with entire villages sometimes leaving en masse for Australia. My father had two sisters, the older, Vincenza who migrated pre-war, and their father who lived with Vincenza, south of the Swan River. Vincenza was blue rinse, drove a shiny red Falcon, wore bright red lipstick and pearl earrings; she was fashionable and very successful as a dressmaker to the Perth’s hoi polloi. We loved her visits, especially as she never left without spoiling us big time with money, chocolates or whatever.

We had many cousins on dad’s side and went to large weddings, or food fests as we saw them where we tore around wildly with our mouths stuffed. Weekend picnics and home visits were common with Italian bowls, or Brigia, featuring and beer flowed freely. Copious amounts of great food and other delicacies were available for our greedy mouths and stomachs. Italians love wine at night, with meals, but beer ruled in the heat of the day. I was offered beer to put hair on my chest. I have avoided beer ever since but hair has grown on my chest regardless.

We didn’t get to meet mum’s relatives although a brother did visit and stay for a short period before moving on to Queensland. I heard that mum was from a lower social class and family history, confirmed in a visit to Italy in 2012, goes that her mother-in-law, an unpleasant woman and cattiva by all accounts, slammed the door in her face when she called to say goodbye prior to catching a migrant ship to Australia. Shocking, as my brother Tony was a newborn baby in mum’s arms on that visit. Fortunately mum didn’t drop him in shock and we all survived this rude departure. Dad had gone to Australia months beforehand to set things up for us, and Aunt Vicenza helped. Another family story is that dad met us at the port of Fremantle when the ship came in and, when he saw us, hurled some bars of chocolate for us to catch but they fell short into the murky waters.

Our family was closest to Pietro and Calogera Lopes, and their three lovely daughters, and any visit to Perth was unthinkable without at least one fantastic meal at their place. Pietro was a bricklayer and also, like his 2nd cousin, dad, a master gardener. He still is and my Sydney family and I still love to visit and be regaled by his fresh vegetables and Lopes women's wonderful dinners.

Our family was closest to Pietro and Calogera Lopes, and their three lovely daughters, and any visit to Perth was unthinkable without at least one fantastic meal at their place. Pietro was a bricklayer and also, like his 2nd cousin, dad, a master gardener. He still is and my Sydney family and I still love to visit and be regaled by his fresh vegetables and Lopes women's wonderful dinners.

I loved swapping comics and collected them with a passion. Both our parents valued education but had insufficient English to assist us with our homework. After all they grew up during the depression, in a poor part of southern Italy, and although they did a few years of high school, and were both literate and numerate, they could only encourage our education from the sidelines. Above all dad didn’t want us to toil as he had, and wearing a tie in an office job, maybe even a career in a bank, was his dream for us boys. In general we exceeded his expectations but not in a bank or in office work.

That said I was an indifferent student in my early teens but passionate about skin diving and underwater swimming generally. An opportunity came up to work in a diving shop so I dropped out of school to take it. It didn’t work out in ways I won’t go into here but my next job as a 15-year-old was an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner, a job I greatly hated: it was straight out of Dickens! In my boredom I dreamt of better things, had a mini-renaissance and decided to resume my education in a serious manner. I put this to mum and dad and they didn’t demur and I returned to the classroom a lot wiser., and them a bit poorer.

Around this time they asked a shopkeeper if I could do some unpaid work, for work experience but above all in order to learn discipline. I complied but was relieved when my time behind a counter ended. It was boring work and I never wanted a career in a small convenience store.

Dad worked hard and led a busy life. As children we never went fishing or camping together although he did love his sport. Carmel recounts that as the eldest, even as a female he would take her to soccer, cycle races, etc. and that one particular race was held at the city edge which in those days was Osborne Park. The race over, dad ran into one of his many mates, who had a ute. With Carmel bundled in middle they drove somewhere to Leederville, where they started to play cards, notwithstanding having a child who hadn't eaten anything bar a piece of fruit. Carmel recalls: “To say that dad was fortunate not to have a frying pan thrown at him would be an understatement.”

Certainly dad liked getting together with his mates for games of cards that sometimes went late into the night, with money changing hands. But he was a responsible gambler. He was not a smoker once his children were born but his mates smoked like proverbial chimneys. I can remember a night when I sat around in the smoky haze, tired and hoping the game would end soon and I could get home to bed. But his mates waved their glasses and money and urged him to play on. It is not my best memory of dad but happened on a single occasion: it is an event I can forgive and overlook. Playing cards was an important social activity for dad’s generation.

Life changed abruptly and our family fortunes took a dive when a drunken driver crashed into dad’s car and left him with serious injuries. I lived in Sydney then, around the time of my sister Carmel’s marriage, when he suddenly couldn’t work as a stonemason, and the family struggled financially on a greatly reduced budget despite mum going to work to supplement it. I sent over what money I could, remembering their concession when they allowed me to resume my education, and eventually he got a compensation payout and monetary relief, but his injured knees and a limp plagued him for the rest of his life, especially on cold winter days. He had to find other employment, so he bought a mower and set up his own lawn mowing business. Suddenly he was a businessman astride a mower, and had a healthy list of customers to service. Serafina continued to work in a hospital kitchen until her retirement. Years earlier she had done long days in seasonal grape picking when Carmel had to step in and look after us. Those days have slipped my memory. But before long our school days came to an end along with mum’s days as a stay-at-home mother.

Dad ended his formal working life as a council street cleaner, work that was easier on his knees and much more relaxing. But his garden and his flowers kept him young and put a spring in his step. He talked and sang to his plants, and he did biological wonders like crossing stems to develop some new breed. He often had people knocking on the door and asking for a cutting. There’s nothing better than a happy gardener getting his green fingers dirty. That kept the smile on his face.

As often happens migrants look nostalgically back to a homeland which has changed over the years, and they dream of a return, and of spending their final days in the old country. Of course the old country of their youth has moved on like the rest of the world, and is barely recognizable. Dad had this dream and returned to Italy on two occasions, one without mum who had other priorities and wasn’t interested. With grandchildren, she simply wanted to stay her ground and continue her life in Australia. She had much more to say, especially in English.

One of the charming and comic aspects of migrants’ life in Australia is how newcomers from many cultures adopt English words, with Italians usually italianising them by adding a final vowel, so bus become buso and car becomes carro, cake become cekee etc. Totally new words are born in this comic way. Italian migrants laugh out loudly at the comedy of Joe Avati as he captures all of these linguistic nuances. Of course Joe Avati kicked his career off in 1990 so my parents never got to hear him, and to roar loudly at his brilliant humour.

We visited Perth in 1984 and they met Cathy for the first time, however, she had to return to work before I did. When I was packed and ready to hug and say goodbye mum was strong but dad got quite emotional and teared up, and mum told him in no uncertain terms to calm down and not make a scene. That was the last time I saw her alive. Mum got gangrene and had her leg amputated at the age of 64. I’ll never forget the early morning phone call that she had died the previous night from a blood clot from her operation. Flying to Perth for her funeral was indeed the saddest time of my life. I wept as never before.

Five months later I married, and dad was present at the wedding and positively beaming. Three years later, on the 25th of February. the exact anniversary of mum’s death, our daughter Helen was born. I thought dad would freak out and be upset but he wasn’t at all. We had lost a mother, he a wife, but had gained a daughter, to cherish, hug and to hold. Sam Oriti lost a mother he shared the same April birthday with, although our naturalisation papers don't say this strangely enough. The papers have her birth on April 25, which is strongly contested by both our parents.

About 3 months after Helen’s birth dad suffered a stroke and lost his sight for a number of days. We were present as he lay dying but Helen, unlike our son Thomas, never met her grandfather. The evening prior to his second stroke he spoke his final words to us as he knew his end was near. He had called out to our mother, then calmed down and asked for some ice cream which as a diabetic he usually wasn’t able to indulge. We spoon fed him like a child.

Then, satisfied, he addressed us formally with our full names told us to all get on together, and to be nice to each other. He was ready to go and we got the call the following morning to come at once. Thirty-six hours later he drew his last breath and was gone. That evening Pietro turned up in tears with a letter dad had entrusted him to deliver upon his death. Which brings to mind The Red Cross message sent to mum in August 1944 that we uncovered in Perth many years later, and which led to these collected memories of past lives.

In memoriam: Leone Oriti 11/12/1914 - 23/5/1989; Serafina Oriti, nee Puglia 20/4/1920 - 25/2/1985

There is a great poem, an epitaph for everyone, by the great Russian poet, Yevgeny Yevtushenko. It is an appropriate ending to this tribute.

People

by Yevgeny Yevtushenko

by Yevgeny Yevtushenko

No people are uninteresting.

Their fate is like the chronicle of planets.

Nothing in them is not particular,

and planet is dissimilar from planet.

And if a man lived in obscurity

making his friends in that obscurity

Obscurity is not uninteresting.

To each his world is private,

and in that world one excellent minute.

And in that world one tragic minute.

These are private.

In any man who dies there dies with him

his first snow and kiss and fight.

It goes with him.

They are left books and bridges

and painted canvas and machinery.

Whose fate is to survive.

But what has gone is also not nothing:

By the rule of the game something is gone.

Not people die but worlds die in them.

Whom we knew as faulty, the earth's creatures.

Of whom, essentially, what did we know?

Brother of a brother? Friend of friends?

Lover of lover?

We who knew our fathers

in everything, in nothing.

They perish. they cannot be brought back.

The secret worlds are not regenerated.

And every time again and again

I make my lament against destruction.

Comments

Post a Comment